Content warning: This article contains images that may be graphic for some readers.

Knowing some basic knowledge of your pelvic anatomy can help you to understand the location of your endometriosis, the symptoms it may cause and what happens when endometriosis is removed during your surgery.

Anatomy 101 for endometriosis

Endometriosis lesions found outside the uterus lead to inflammation during periods that can cause pelvic pain as well as scarring around pelvic organs. In some cases, lesions can affect fertility.

Endometriosis is classified into 3 different types and these might in fact be different diseases. There are many ways of classifying endometriosis, and no single system is used by everyone – it’s annoying we know.

- Superficial endometriosis deposits are small, speckled patterns that sit on the lining of the pelvic cavity called the peritoneum. They do not invade deep into the tissue and can occur anywhere – including on the pelvic organs.

- Ovarian Endometriosis are lesions on the ovaries that can lead to cysts forming in the ovary. It’s called an endometrioma or a “chocolate cyst” because the fluid in the cyst is thick and dark brown. It sounds a bit gross, but it looks a lot like melted dark chocolate.

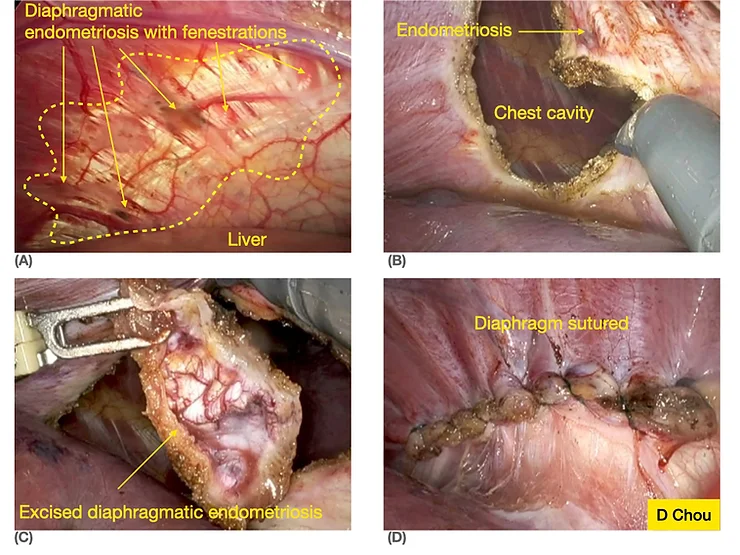

- Deep Infiltrative Endometriosis is more aggressive and can spread into different areas of the pelvis. This includes the wall of the vagina, bowel, bladder and ureter (the tube that comes from the kidney into the bladder). It can also spread into tissues that are outside the pelvis including the diaphragm (the muscle that separates the chest and the abdomen)

Let’s look at the anatomy of the pelvis to help us understand where endometriosis occurs and what that means for surgery.

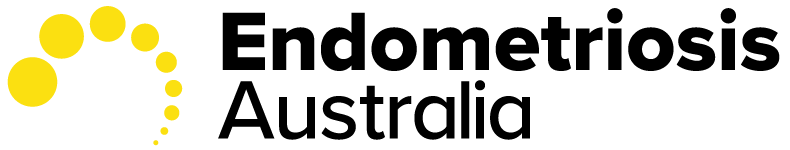

Fig 1. This picture shows a normal pelvis. The labels are the technical terms you would see in an anatomy textbook. We will explain each term below to make your diagnosis easier to understand.

Uterus/Womb

A thick-walled, pear-shaped muscular organ where a baby is carried during pregnancy. (Fig 1). This is also where periods come from as the lining is shed – usually each month unless you are on hormonal treatment. Endometriosis can cause the uterus to be stuck to surrounding organs in the pelvis including the ovaries and the bowel. Endometriosis that affects the muscle of the uterus called adenomyosis, can also cause painful periods.

Ovaries

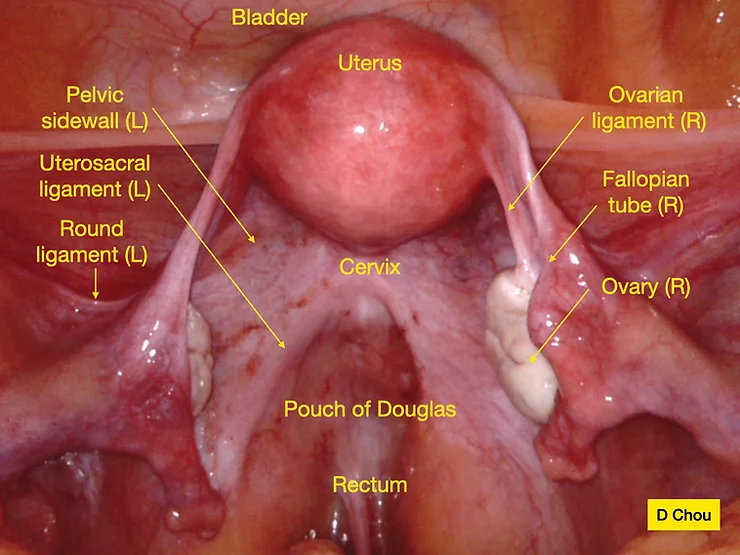

These are the female reproductive organs. They produce both eggs and the hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle. The ovaries attach to the uterus by a thin fibrous structure called the ovarian ligament. This ligament means that the ovaries are usually very mobile and sit behind the uterus. In people who have endometriosis that affects the ovaries, they can get stuck to other structures in the pelvis. This can include the walls of the pelvis, the uterus and each other. An ‘endometrioma’ is a cyst that is formed when endometriosis occurs on and around the ovary (Fig 2).

Fig 2. These are photos of an endometrioma or chocolate cyst being removed.

Fallopian Tubes

The thin hollow structures that lead from the uterus and open near the ovaries. The opening of the fallopian tubes near the ovaries are called fimbria. These delicate finger-like structures help ‘sweep’ the egg once it is released from the ovary into the tube. The Fallopian tubes are the highway for the egg and sperm to meet. In women with endometriosis, the fallopian tube can become scarred and this may mean they are not able to move freely. The tubes may also be blocked and filled with fluid. All of these can affect fertility.

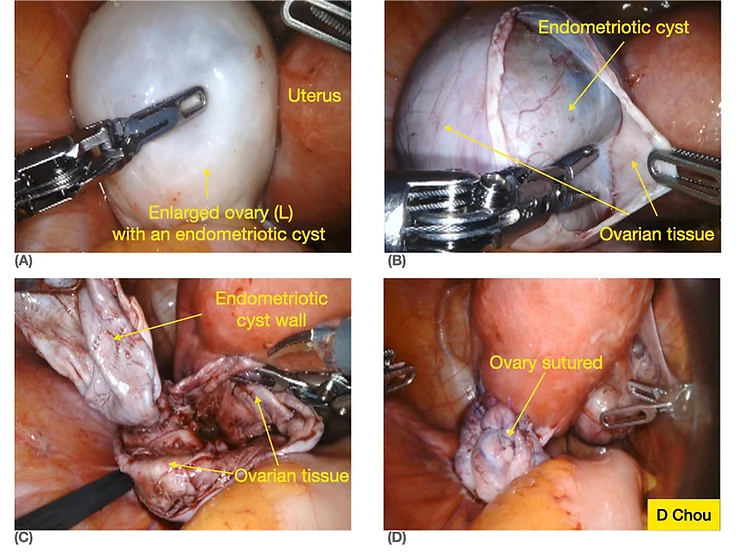

Pelvic sidewalls

The bones that form the walls have many soft tissues on their inside. The ‘sidewalls’ are where important structures like blood vessels and the ureter pass from the abdomen into the pelvis. The bones provide protection on the outside to these structures. The pelvic sidewalls are the most common areas where endometriosis occurs on what is called the peritoneum. The peritoneum is a very thin lining layer of tissue that is found in the pelvis and the abdomen. When there is endometriosis in the peritoneum of the sidewall, the ovaries can become stuck to it. With more inflammation and changes in hormone cycles, this can lead to an endometrioma that involves the ovary and the side wall. Endometriosis lesions can also be located directly over the ureter (Fig. 2).

Fig 3. Removal of pelvic side wall endometriosis

Cervix and retrocervical area

The cervix is the lowest part of the uterus and is part of the uterus itself. The cervix is sometimes referred to as the neck of the womb. Its role is to keep the uterus closed during pregnancy until labour occurs. The ‘retro-cervical’ area is the back wall of the cervix and it can be affected with endometriosis that builds up and causes scarring. Endometriosis in this retrocervical area means that the scarring folds the uterus back towards itself in a bend. This can be seen on an ultrasound that may report a ‘retroflexed’ or ‘retroverted’ uterus. When this is found, a more detailed look into the area can help make the diagnosis of endometriosis.

Uterosacral ligaments

The uterosacral ligaments are the strong muscular and fibrous tissues that hold the uterus to the back-bone. They connect the cervix to the sacrum – the triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms the back of the pelvis. The uterosacral ligaments provide support for the uterus and prevent it from moving too low. The uterosacral ligaments are very close to the vagina (and can be felt during a vaginal examination) and the bowel. Women with endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments can suffer from painful sex and painful periods as the ligaments become scarred and stuck to surrounding structures.

Pouch of Douglas/Cul de sac/rectouterine pouch

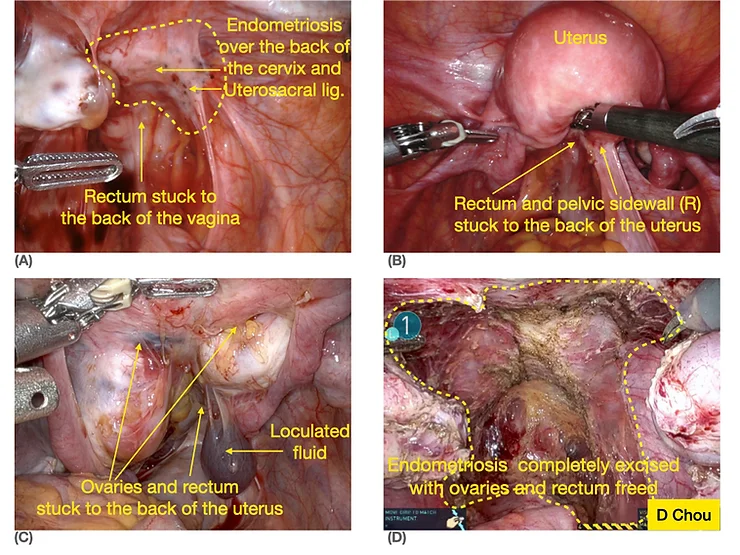

These are all the terms used to describe the U-turn space between the back of the vagina and the uterus in the front and the bowel (the rectum) at the back. It forms the deepest part of the pelvis. There is often a small amount of fluid in this area that can be seen on an ultrasound and this is normal. Sometimes with endometriosis deposits, this space can be affected by scarring and there is no longer a space there. This is called ‘obliteration of the cul de sac’ (Fig 4) and is a sign of severe endometriosis. Sometimes, the ovaries and rectum are stuck onto the back of the vagina and uterus in this area. Obliteration of the pouch of Douglas is described as partial or complete depending on how much the organs are stuck. Surgery for a completely obliterated Pouch of Douglas can be quite challenging. It requires freeing all the pelvic organs and removing all the disease and scarring. Patients with endometriosis affecting the pouch of Douglas can suffer from painful periods, bowel symptoms (like painful bowel motions), infertility and painful intercourse.

Fig 4. Obliteration of Pouch of Douglas

- (A) & (B) Partial obliteration of Pouch of Douglas

- (C) & (D) Complete obliteration of Pouch of Douglas (C) before and (D) after removal of endometriosis and freeing of ovaries and rectum.

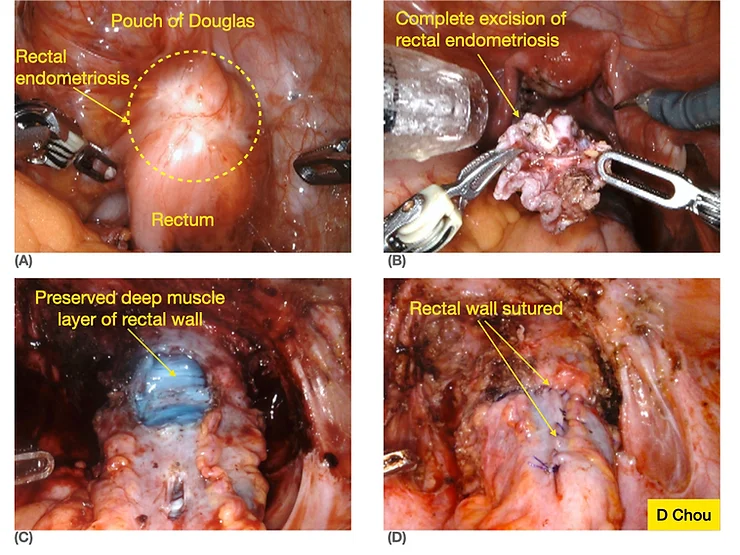

Rectum

The rectum is the lower part of the large bowel and forms the back of the Pouch of Douglas before it travels behind the vagina and then becomes the anus. The rectum is the most common area of the bowel affected by endometriosis. There are 3 layers to the bowel wall and endometriosis lesions can invade into just one, or all 3 of these layers.

There are 3 types of bowel procedures for rectal endometriosis, these are:

- Rectal shaving: Involves removal of bowel endometriosis from the bowel wall without entering the bowel

- Disc excision: Consists of removing a full-thickness area of the bowel wall.

- Segmental bowel resection: When a length of the bowel is removed and either end is rejoined together.

The size of the endometriosis lesion and how deep into the bowel the disease has spread will determine which procedure is performed.

A specialised, preoperative Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis ultrasound will often be performed prior to surgery to accurately identify the lesions. Your gynaecologist may refer you to a specialised bowel surgeon to assist in the removal of bowel endometriosis.

Bladder and uterovesical fold

The bladder sits in front of the uterus and stores the urine produced by the kidneys. The kidneys are joined to the bladder by the ureters. The bladder and ureters can be affected by both superficial and deep endometriosis lesions. When there is severe bladder or ureter endometriosis, a specialist surgeon called a urologist may be required for the surgery in addition to your gynaecologist.

The ‘uterovesical fold’ is the lining that sits over the bladder and lower uterus. It is usually a very open space with no scar tissue, although if someone has had a caesarean delivery, there is always scarring in this area. In some people with endometriosis, the space between the bladder and uterus becomes stuck together by scar tissue and endometriosis tissue. It can cause pain and in severe cases, bleeding into the bladder.

Round ligaments

These are thick fibrous and muscular tissues that come out the top of the uterus (at the opposite end to the cervix) and connect the uterus to the groin. There is one round ligament on each side of the uterus. The main function of the round ligaments is to stop the uterus from twisting on itself. Endometriosis can affect the round ligaments, but less commonly than in other areas of the pelvis.

Extra-pelvic endometriosis

Endometriosis that affects organs and tissues outside the pelvis is less common than in the pelvis. The appendix, the diaphragm (Fig. 6) and other areas of the bowel are areas where endometriosis can grow.

In summary

An idea of your pelvic anatomy can help you to understand the location of your endometriosis, the symptoms it may cause and what happens when endometriosis is removed during your surgery.

References

- Chou D, Perera S, Bukhari M, Al-Shamari M, Cario G at al. Rectal Shaving for Bowel Endometriosis by Laparoscopic Reverse Submucosal Dissection for Easier, Safer and More Complete Excision of Disease. JMIG. 2021 Oct; 28(10):1679

Written by:

Dr Jessica Robertson, Dr Aoife McSweeney, Dr Dave Listijono, Dr Assem Kalantan, Dr Danny Chou