By Dr Michael Wynn-Williams – Endometriosis Australia’s Clinical Advisory Committee

Endometriosis is most commonly thought of as a condition affecting the reproductive organs, this is not exclusively the case. Endometriosis can also involve the bowel. As with pelvic endometriosis, symptoms of bowel endometriosis can range from non-existent to severely debilitating, where the pain interferes with multiple facets of normal daily life. As with disease in the pelvis, endometriosis involving the bowel has been shown to have a possible effect on a woman’s fertility.

The severity of endometriosis is generally rated between stage I–minimal disease to stage IV–severe disease, with stage II–mild and stage III–moderate. Bowel endometriosis would generally be classified as stage IV and possibly affects up to 1 in 100 women in their reproductive years.

The majority of women with endometriosis can experience a number of bowel-related symptoms, but reassuringly only a few of these women will have endometriosis that has spread to the bowel. The symptoms of endometriosis generally include painful periods, pelvic pain, painful sex, back ache, bladder and bowel symptoms. Bowel symptoms are very common and include diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal cramps and bloating. These symptoms can occur prior to, during or after the period, or at any time in the cycle. The symptoms that should give the most concern regarding endometriosis in the lower part of the bowel are severe rectal pain during a bowel motion (dyschezia) or rectal bleeding when you have your period. The symptoms related to endometriosis in the higher parts of the bowel can vary but could include intermittent or constant right pelvic pain, or even small bowel obstruction.

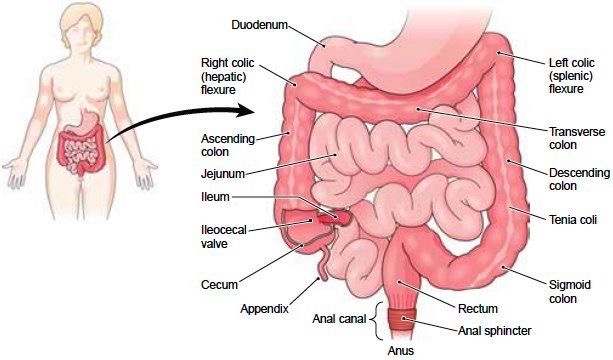

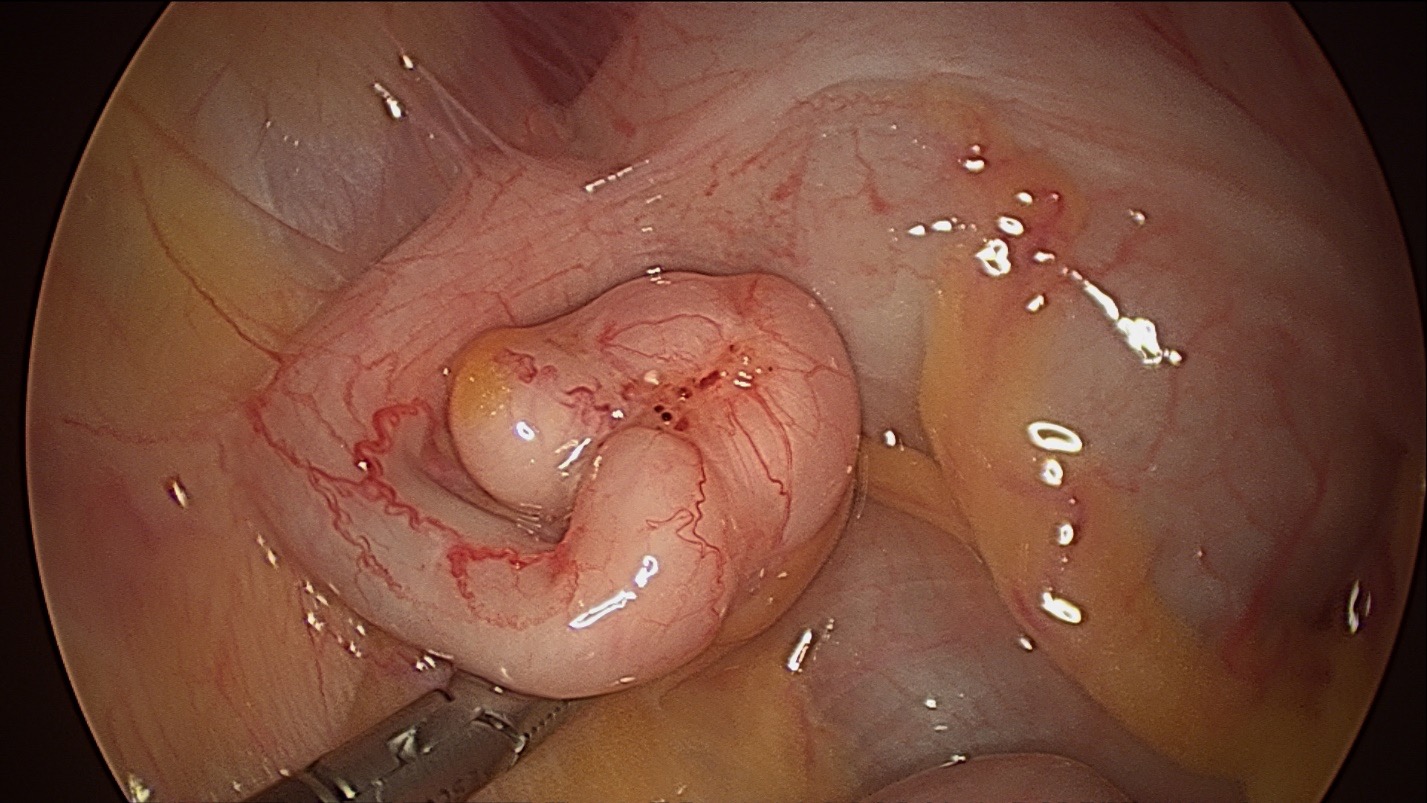

The bowel (Figure 1) is part of the digestive system that is involved in absorbing nutrients and water from the food that we eat and drink. The large bowel (caecum, sigmoid and rectum) is responsible for the final absorption of water and storage of faecal matter before it is passed as a bowel motion. The majority of bowel endometriosis (80-90%) is found in the final 20cm (between the rectum and the sigmoid colon). The rest is found in the appendix (Figure 2), the caecum, and the small bowel (ileum). There are a number of theories as to how endometriosis forms in the pelvis and in the bowel, and these will be covered in a future blog.

Figure 1 -The bowel anatomy

Figure 2 -Endometriosis on the Appendix

When women present to their health professional with symptoms related to period pain, particularly with those that are bowel-related, there’s a lot of variance in how they will be managed or referred. A general practitioner will refer a woman depending on the symptoms she presents with, the findings on examination and the tests performed. Patients will often be sent to a Gastroenterologist (a bowel physician) to investigate the possibility of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). If rectal bleeding is an issue they may be sent to a Colorectal Surgeon (a bowel surgeon) for a colonoscopy (a flexible camera that looks in the large bowel) to rule out bowel polyps or bowel cancer. Ideally, a woman will be sent to a general gynaecologist or a gynaecologist who specialises in endometriosis to be diagnosed as soon as possible.

At the first gynaecologist appointment, the specialist will take a detailed history looking for the common symptoms mentioned above, and will perform a physical examination looking for physical evidence of endometriosis. Examination of the vagina may reveal tenderness, firmness or a mass in the normally soft area at the very top of the vagina behind the cervix. This could indicate rectovaginal endometriosis. On occasions, a rectal examination may be performed. A transvaginal ultrasound may also be performed at the examination, or a woman may be referred to an ultrasound specialist to look for evidence of bowel endometriosis. In skilled hands, endometriosis in the rectum may be visualised in many cases. Another form of imaging that is used less often but can be useful is MRI.

While transvaginal ultrasound is very useful, currently the majority of patients in Australia with bowel endometriosis will have it diagnosed at laparoscopy. The finding of endometriosis on the bowel may be expected or unexpected. If the findings are unexpected, the disease will be documented with photos or video and then the woman can be referred onto an endometriosis specialist who will work with a multidisciplinary team for treatment. This team may include a colorectal surgeon, a urologist, specialist physiotherapists and nurses. It is hoped in the future that most bowel endometriosis could be diagnosed without a laparoscopy, and women would be referred straight to an endometriosis specialist.

Once the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis is made, it is important that the woman is fully informed about endometriosis, where it is, and what her management options are. When endometriosis is in the bowel, it is highly likely that there is also endometriosis in the more common sites of the pelvis, such as the pelvic sidewall (under the ovaries), the pouch of Douglas (the space between the cervix and the rectum), the ovaries (endometrioma) and the bladder. Whatever management option is planned, it is important that these areas are addressed as well. Endometriosis in the bowel generally means the stage of the disease is severe, so treatment options may be significantly limited. It is important that the woman is fully informed of all her treatment options and that she makes decisions based on the symptoms that she experiences.

Management of lifestyle factors and complementary therapies (acupuncture, naturopathy, herbal therapies) can have a place for some women in the management of bowel endometriosis with minimal symptoms. While evidence is lacking, some women may experience enough benefit that their functioning may improve. Medical management with hormonal suppression, either the combined contraceptive pill, oral progestins or total hormonal suppression with menopausal-inducing medication (GnRH agonists), can play a role for some patients. Many patients have been on hormonal suppression for many years at presentation to a specialist. GnRH agonists can only be used for short periods of time (maximum six months) and can have significant side effects.

In Australia, the main treatment option for women with significant symptoms is a laparoscopic resection of severe endometriosis in the hands of an endometriosis specialist, working with a multidisciplinary team. Any surgery will involve careful assessment and planning, looking at where the endometriosis is in the pelvis and in the bowel. The size and location of the lesions will dictate the management. The specialist will discuss the planned surgery and obtain informed consent from the woman, indicating that she understands the operation to be performed, and the risk and benefits involved. The risks involved in having bowel endometriosis excised are increased over that of normal endometriosis surgery, but in skilled, experienced hands these are still small compared to the benefit of significant symptom relief. The most serious risks of this complex surgery include leakage of the bowel contents from where the bowel endometriosis was removed (potentially life threatening), requiring an ileostomy (a temporary bag that drains the small bowel contents), and damage to the urinary system (bladder and ureters).

The woman may be referred to other members of the team prior to surgery, such as a colorectal surgeon. This surgeon may recommend a colonoscopy or a sigmoidoscopy at some point prior to the planned surgery. A woman may also be required to have a bowel preparation to empty the bowel prior to surgery, but this practice is occurring less often as evidence is showing that it has little benefit.

Laparoscopic resection of endometriosis is performed through a number of small holes in the lower abdominal wall. A laparoscope (camera) is placed through a hole in the belly button. The pelvic endometriosis is generally excised before any bowel endometriosis is managed. It is generally accepted that rectal endometriosis of less than 2-3cm in size can be managed by cutting it out of the rectal muscle and the defect repaired with sutures (rectal shaving). This is often performed by an endometriosis specialist without a colorectal surgeon involved. Slightly larger and deeper rectal lesions may be removed with a disk resection by a colorectal surgeon using a special stapling device. Multiple lesions or larger lesions may require a segmental resection (removing 10-15cm of the rectum or sigmoid and re-joining the cut ends). Endometriosis on the appendix is removed by performing an appendicectomy. Caecal endometriosis may require removal of part of the caecum and the terminal ileum (right hemicolectomy). Small bowel endometriosis that is symptomatic may require a small segment to be removed. Once the surgery is complete the hospital stay may be longer (2-7 days) if portions of bowel were removed. It may take a few days for the bowel to return to normal function.

There is growing evidence that women who have significant fertility issues and coexisting severe bowel endometriosis can improve their fertility by having the endometriosis removed. Endometriosis affects fertility in many ways, and these will be covered in future blogs. Some women who have completed their fertility may choose to have a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) at the same time as having their bowel endometriosis removed. There is generally no benefit in just having a hysterectomy and leaving the symptomatic bowel endometriosis alone. It is generally recommended that the ovaries should be preserved if possible.

Once the bowel endometriosis has been removed the recurrence rate is low. Shaving endometriosis off the rectum has a higher recurrence rate than performing a segmental resection as not all the endometriosis may have been removed. Even so, it is often better to shave bowel endometriosis where possible rather than perform a segmental resection. This is because segmental resections can have a significant effect on how the bowel functions, which may take up to a year before returning to normal. But, in cases where segmental resection is deemed necessary, most patients find this more acceptable than the symptoms they were experiencing before the surgery. Pelvic pain may return in up to 50% of women after five years, with about 30% of women developing further endometriosis.

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis can be very debilitating and have a major effect on multiple facets of a woman’s life. For women who believe they may be suffering from endometriosis of the pelvis or bowel, the first step is to have a discussion with a GP who can refer on for further investigation.