By Dr Michael Wynn-Williams – Endometriosis Australia’s Clinical Advisory Committee

Endometriosis is the presence of tissue similar to that of the endometrial lining that grows outside the uterus. It is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting up to one in seven girls, women, transgender individuals, and non-binary people who may not identify as women. While many think of endometriosis as only affecting the reproductive organs, it is actually more varied. It can also involve the bowel. Like pelvic endometriosis, the symptoms of bowel endometriosis can range from no symptoms at all to very severe pain that significantly impacts daily life. Similarly to pelvic endometriosis, it may also affect fertility. Recognising this broader view can help in better understanding and managing the condition.

Endometriosis can range from stage I, which is minimal, to stage IV, which is severe, with stage II considered mild and stage III moderate. Bowel endometriosis is typically classified as stage IV and may affect between 5% and 20% of patients during their reproductive years.

Many patients with endometriosis notice a range of bowel-related symptoms, and thankfully, only a small number have the condition that spreads to the bowel. Typical signs of endometriosis include painful periods, pelvic discomfort, painful sex, backaches, and bladder or bowel issues. Bowel symptoms are quite common and might include diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal cramps, and bloating. These can occur before, during, or after your period, or at any point during your cycle. Of particular concern are symptoms like severe rectal pain during a bowel movement (dyschezia) or rectal bleeding during your period, which could indicate endometriosis in the lower bowel. Symptoms from endometriosis in the upper parts of the bowel can also vary and may include occasional or persistent right-sided pelvic pain or even small bowel obstruction.

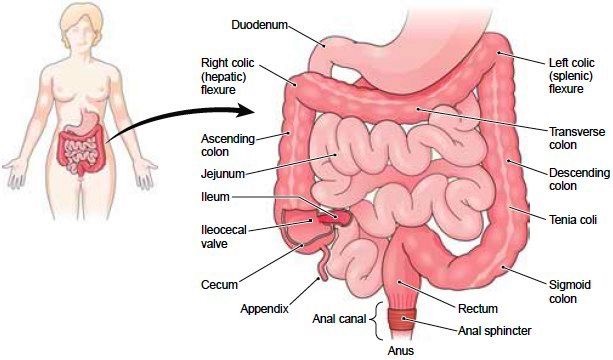

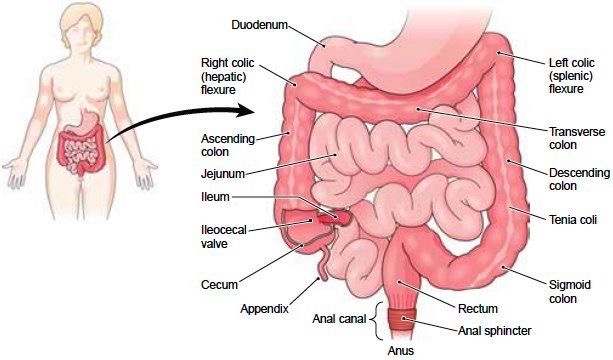

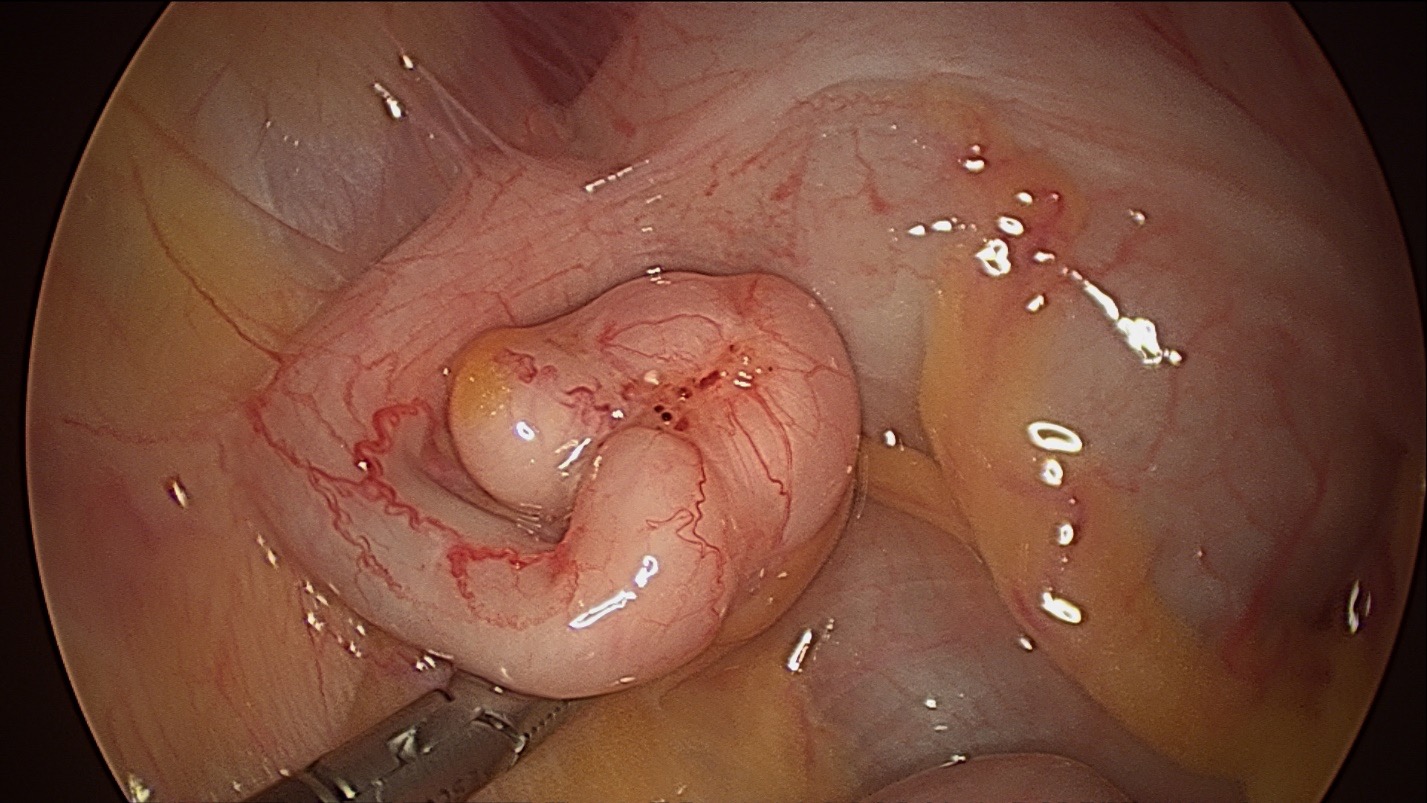

The bowel (Figure 1) is a vital part of our digestive system, helping us absorb nutrients and water from the food and drinks we enjoy. The large bowel—comprising the caecum, sigmoid, and rectum—plays a key role in final water absorption and storing faecal matter before it’s expelled as a bowel movement. Interestingly, about 80-90% of bowel endometriosis occurs in the last 20cm, between the rectum and sigmoid colon. The remaining cases can be found in the appendix (see Figure 2), the caecum, and the small bowel (ileum). There are several theories about how endometriosis develops in the pelvis and bowel, and these have been explored in other Endometriosis Australia blogs.

Figure 1 -The bowel anatomy

Figure 2 – Endometriosis on the Appendix

When someone visits their health professional with symptoms related to period pain, especially if bowel issues are involved, the approach to their care can vary quite a bit. A general practitioner will decide to refer someone based on their symptoms, examination findings, and test results. Often, patients are referred to a Gastroenterologist, who specializes in bowel conditions, to check for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). If rectal bleeding is a concern, they might be referred to a Colorectal Surgeon, a specialist in bowel surgery, for a colonoscopy—a procedure where a flexible camera looks inside the large bowel—to rule out bowel polyps or bowel cancer. Ideally, they should be directed to a general gynaecologist or a gynaecologist with expertise in endometriosis to get a diagnosis as quickly as possible.

At the first gynaecologist appointment, the specialist will take a detailed history focusing on common symptoms mentioned earlier and will perform a physical examination to look for evidence of endometriosis. Examination of the vagina may reveal tenderness, firmness, or a mass in the usually soft area at the very top of the vagina behind the cervix. This could suggest rectovaginal endometriosis. Occasionally, a rectal examination may be performed. During the examination, a transvaginal ultrasound might be done, or you could be referred to a pelvic ultrasound specialist who will check for signs of bowel endometriosis. Experienced ultrasound practitioners often find that endometriosis can be seen in the rectum. Pelvic MRI is a valuable tool in diagnosing and understanding the extent of bowel endometriosis. It’s also important to remember that if an ultrasound or MRI is negative, it doesn’t always mean endometriosis isn’t present—sometimes, it just requires a closer look.

While transvaginal ultrasound is incredibly helpful, in Australia, most patients with bowel endometriosis are currently diagnosed through laparoscopy. Finding endometriosis on the bowel can sometimes be expected, but other times it may come as a surprise. If the diagnosis is unexpected, doctors will document the findings with photos or videos, and then the patient can be referred to a specialist who works with a team of experts—such as a colorectal surgeon, urologist, physiotherapists, and nurses—to provide the best care. Looking ahead, we hope that in the future, most cases of bowel endometriosis can be diagnosed without needing surgery, allowing people to be directly referred to an endometriosis specialist for prompt treatment. This recommendation is reflected in the latest RANZCOG Australian Endometriosis Guideline from 2025.

Once a diagnosis of bowel endometriosis is confirmed, it’s really helpful to ensure the patients understand everything about endometriosis—such as what it is, where it’s located, and what management options are available. When endometriosis is in the bowel, it’s quite common that it also affects other parts of the pelvis, like the pelvic sidewall (under the ovaries), the Pouch of Douglas (the space between the cervix and the rectum), the ovaries (known as endometrioma), and the bladder. No matter which management plan is chosen, it’s important to consider these areas as well. Usually, bowel endometriosis indicates that the disease is quite advanced, which can limit treatment options. That’s why it’s so important for the patient to be well-informed about all their options, so they can make decisions that best fit their symptoms and personal situation.

Managing lifestyle factors and exploring complementary therapies like acupuncture, naturopathy, and herbal therapies can be beneficial for some people with bowel endometriosis who experience minimal symptoms. While research is still ongoing, some individuals may find these approaches help improve their daily functioning. Medical options such as continuous low-dose contraceptives or progestins like norethisterone are often used to support this condition comfortably. Many patients find Dienogest (Visanne), available in Australia, to be better tolerated and more effective than other progestins, making it a popular choice. These medications can often be used long-term if well accepted. For short-term relief, a GnRH agonist like Zoladex might be helpful for up to six months, especially when combined with estrogen and progestin hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to support bone health and manage menopausal symptoms. Recently, Australia has introduced Ryeqo, a new oral GnRH antagonist (Regugolix) with built-in HRT, which could be a helpful option for long-term symptom management.

In Australia, the main approach for treating people with significant symptoms involves a laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery to remove severe endometriosis, performed by a specialist in endometriosis working with a caring, multidisciplinary team. Before surgery, there will be thorough assessments and careful planning, including understanding where the endometriosis is located in the pelvis and bowel. The size and placement of the lesions help guide the management plan. The specialist will talk through the upcoming surgery and make sure patients fully understand the procedure, along with its risks and benefits. While removing bowel endometriosis carries higher risks compared to general endometriosis surgery, these risks are still small when handled by experienced, skilled surgeons, especially considering the potential for significant symptom relief. The most serious concerns with this complex surgery include the possibility of bowel content leakage (which can be life-threatening), the need for a temporary ileostomy (a bag that drains the small bowel), or injury to the urinary system, such as the bladder or ureters.

The patient will probably be referred to other team members before surgery, such as a colorectal surgeon. This surgeon might suggest a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy at some stage before the scheduled surgery. Patients may also need to have bowel preparation to clear the bowel before surgery, although this practice is used less often now as evidence shows it provides little benefit.

Laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery for endometriosis involves making a few small incisions in the lower abdomen. A tiny camera, called a laparoscope, is inserted through a small opening in the belly button to guide the procedure. Typically, the endometriosis in the pelvis is carefully removed first, before addressing any bowel involvement. For smaller rectal endometriosis, less than 2-3cm, it can usually be safely shaved out of the rectal muscle and repaired with stitches—this is often done by an expert in endometriosis without needing a colorectal surgeon. Slightly larger or deeper rectal lesions might be removed through a disk resection performed by a colorectal surgeon using a special stapling device. If there are multiple or larger lesions, sometimes a segment of the rectum or sigmoid colon (about 10-15cm) needs to be removed and reconnected. Endometriosis on the appendix can be treated by removing the appendix, known as an appendicectomy. In some cases, if the caecum is involved, a part of it along with the terminal ileum might need to be removed, which is called a right hemicolectomy. Symptomatic endometriosis on the small bowel might also require removing a small segment. After the surgery, the length of your hospital stay can vary from 2 to 7 days, especially if parts of the bowel needed removal. It may take a few days for your bowel to fully return to normal function.

There’s encouraging evidence that people facing significant fertility challenges along with severe bowel endometriosis, can often boost their chances of pregnancy by having the endometriosis treated and removed. Endometriosis can impact fertility in various ways, which we’ve discussed in other blogs by Endometriosis Australia. For those who do not desire future fertility or who have finished having children, a hysterectomy—the removal of the uterus—might be an option alongside the removal of bowel endometriosis. However, simply having a hysterectomy without addressing the bowel endometriosis usually doesn’t offer additional benefits. In most cases, doctors recommend preserving the ovaries if possible to support overall health.

Once the bowel endometriosis has been successfully removed, the chances of it coming back are quite low. Shaving off endometriosis from the rectum tends to have a higher chance of recurrence compared to doing a segmental resection, since not all of the endometriosis might be eliminated this way. However, many specialists prefer to shave bowel endometriosis whenever possible, rather than opting for a segmental resection. This is because segmental resections can significantly affect bowel function, sometimes taking up to a year for everything to return to normal. When a segmental resection is necessary, most patients find it more acceptable than enduring the symptoms they experienced beforehand. It’s worth noting that pelvic pain may come back in up to 50% of women after five years, and around 30% may develop additional endometriosis.

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis can be quite challenging and significantly impact various aspects of an individual’s life. If you think you might be experiencing endometriosis affecting the pelvis or bowel, the best first step is to talk with your GP. They can guide you and arrange for further tests to get to the bottom of it.

Written by,

Dr Michael Wynn-Williams

Revised August 2025

Auckland, New Zealand