Warning: This post contains surgical imagery that some may find graphic.

Endometriosis is the presence of tissue similar to that of the endometrial lining that grows outside the uterus. It is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting up to one in seven girls, women, transgender individuals, and non-binary people who may not identify as women. Most cases occur in or around the pelvic organs, the pelvic peritoneum, and the ovaries. About 12% of individuals develop endometriosis higher in the pelvis (known as extra-pelvic endometriosis) or in the lower abdomen, affecting the bowel wall (rectum, sigmoid, caecum, small bowel). It is estimated that fewer than 2% develop endometriosis around the right side of the liver and diaphragm. A smaller and undetermined number of people have endometriosis in the chest (thorax) or lungs, known as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome (TES). The true prevalence of this form remains unknown, as little research has been conducted beyond case reports in the medical literature.

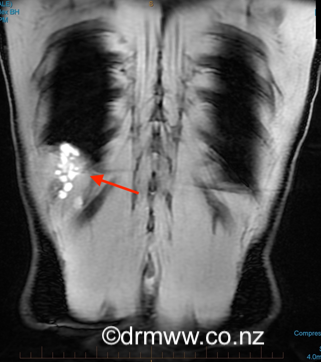

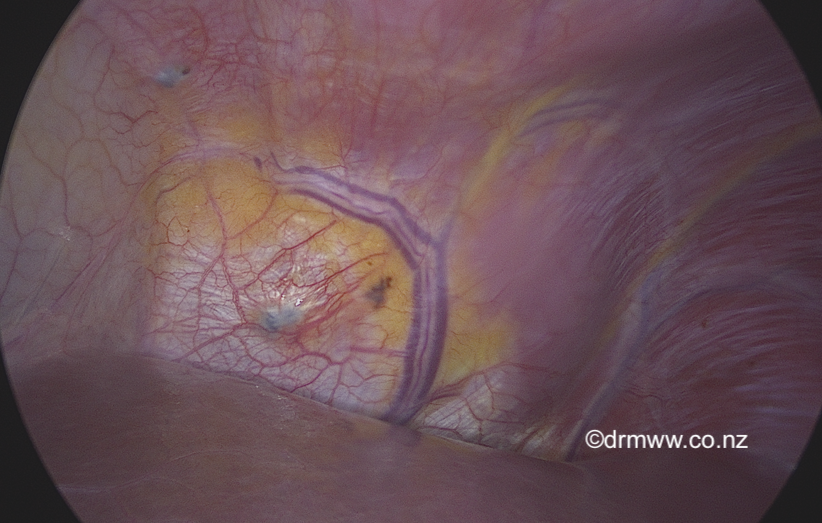

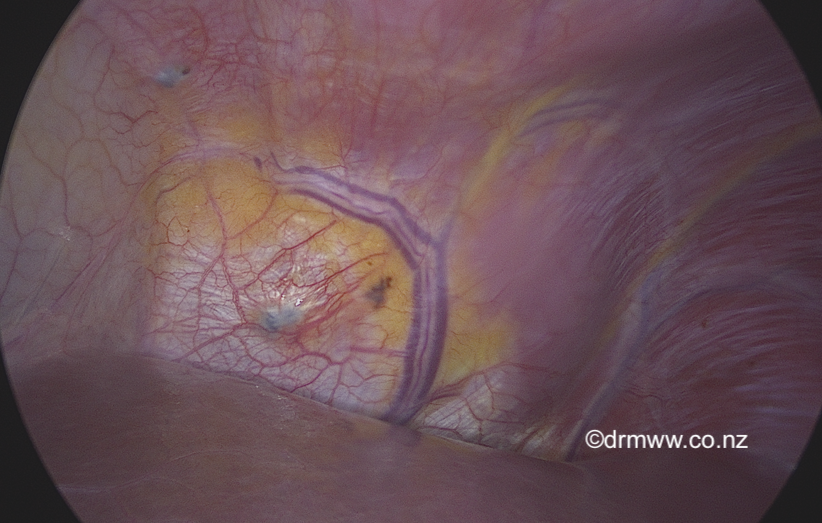

This blog will explore endometriosis of the diaphragm (Image 1) and thorax (Image 2). Even though endometriosis in these areas isn’t often diagnosed, it’s a crucial topic because of the challenging symptoms people may experience there. Additionally, finding specialists who are knowledgeable and confident in managing care for these conditions can be quite difficult, making this a valuable discussion.

Image 1 & 2 The anatomy of the Diaphragm and Thorax

When endometriosis impacts the upper abdomen and diaphragm, the symptoms can really differ from person to person. Many isolated lesions might not cause any noticeable symptoms at all. For some, they might feel a slight ache in the right shoulder around their menstrual period, while others could experience more intense effects like cyclical difficulty when taking deep breaths or sitting upright, or severe pain that radiates from the shoulder to the shoulder blade.

The diaphragm is a vital muscle and connective tissue layer that separates the abdominal cavity from the thoracic cavity. It’s closely connected to the upper abdominal organs like the liver and spleen. Right above it are the bases of the lungs and the heart’s sac (pericardium). The diaphragm is controlled by cranial nerves C3, 4, and 5, which help it move so you can breathe. Interestingly, if there’s pain from the diaphragm, you might actually feel it in your shoulder blade and shoulder area. Sometimes, pain in your neck or even your ear can occur because of the shared nerve (phrenic nerve). The diaphragm is just a few millimetres thick, and if endometriosis develops there, it can form adhesions with the liver and reach the pleural cavity around the lungs. That’s why taking deep breaths during your period might sometimes be uncomfortable or painful.

Image 3 – endometriosis on left diaphragm under the heart.

Endometriosis inside the chest cavity mainly occurs when lesions pass through the diaphragm. Around 40% of these lesions are found in the lung and can lead to symptoms like cyclical (catamenial) chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, or haemoptysis (coughing blood). In rare cases, this condition can cause serious issues such as spontaneous lung collapse (pneumothorax) or bleeding into the space around the lungs (haemothorax).

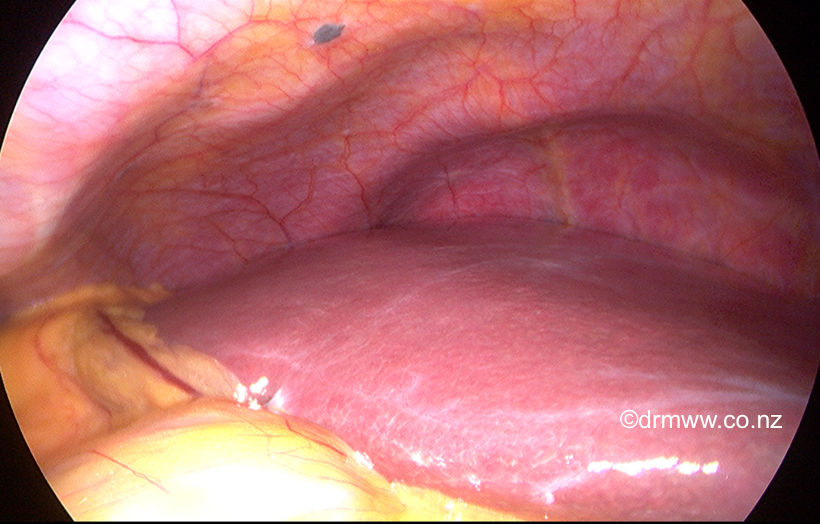

Image 4 – typical mild-spot endometriosis on the edge of the right diaphragm.

We may not fully understand why endometriosis appears in the pelvis, or even in the diaphragm and thorax, but researchers have some interesting ideas. Several theories might explain why it grows in areas far from the pelvis. The most supported explanation relates to embryological cell displacement or coelomic metaplasia. For those interested, the theories behind endometriosis development are also discussed in the Endometriosis Australia blogs. Interestingly, about 85% of people with diaphragmatic endometriosis or TES also have pelvic endometriosis. Most cases, around 90%, are found on the right side.

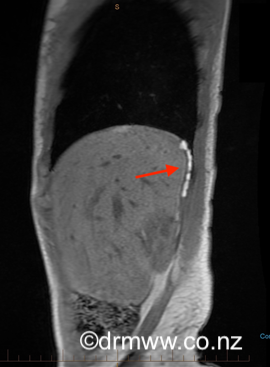

An experienced Endometriosis Specialist usually makes the initial diagnosis by considering the patient’s symptoms along with a thorough history and examination. Because the symptoms can be quite unusual, it’s common for individuals to see various specialists first, such as Cardiothoracic Surgeons, Chest Physicians, or Physiotherapists, before arriving at a diagnosis. Often, many investigations and imaging tests might not show any abnormalities. Chest X-rays and CT scans are commonly done to rule out more common conditions that could explain the symptoms. To confirm the diagnosis more accurately, an MRI performed by an experienced Radiologist is recommended. The best images tend to be captured during a woman’s menstrual period. If the endometriosis lesions are large enough, they can appear as bright white spots (see image 5 & 6).

Image 5 & 6 Posterior diaphragmatic endometriosis seen on MRI as white spots

Detecting endometriosis on the diaphragm is often best done through laparoscopic, which is also how we sometimes discover endometriosis in this area without any symptoms showing. One challenge with laparoscopy is that typically only the front half of the diaphragm can be seen (refer to image 7). For those less experienced, identifying endometriosis on the diaphragm can be tricky. If a patient experiences cyclic blood in cough, a respiratory specialist might perform a bronchoscopy—using a camera to look down the windpipe and into the lungs. This procedure can be complex, and since the lesions are usually tiny and may be obscured by blood, they can be hard to spot. In cases where endometriosis is present on the outer surface of the lungs, an experienced cardiothoracic surgeon can examine it using a laparoscope inserted into the chest cavity, known as Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS).

The management of diaphragmatic endometriosis and TES is generally conservative. Managing this condition can often be comfortably supported with options like continuous low-dose contraceptives or progestins such as norethisterone. Many find that Dienogest (Visanne), which is available in Australia, is better tolerated and more effective than other progestins, making it a popular choice. These medications can be used long-term if they’re well accepted. For short-term relief, a GnRH agonist like Zoladex might be helpful for up to six months, especially when combined with estrogen and progestin hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to support bone health and manage menopausal symptoms. Recently, Australia has welcomed Ryeqo, a new oral GnRH antagonist (Regugolix) with built-in HRT, which could be used for long-term symptom management. Most people discover that their symptoms can be effectively managed with medication. However, if hormonal treatments aren’t suitable, whether due to side effects or personal plans to conceive, surgery might be the next step.

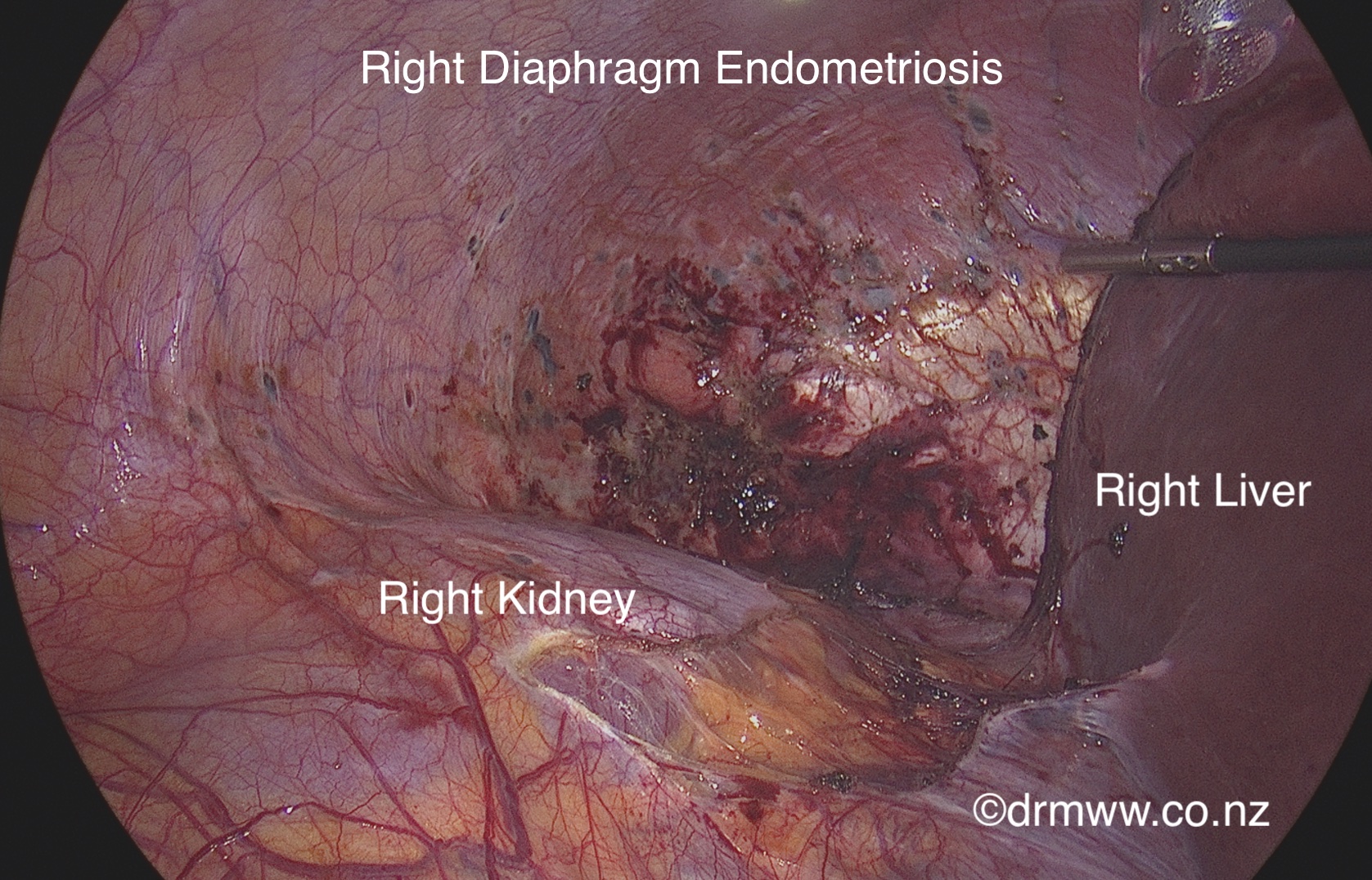

Image 7 Right diaphragm endometriosis seen clearly once the right side of the liver has been mobilised

urgery on the diaphragm or chest cavity is best performed by an experienced Endometriosis Specialist who will work closely with a Hepato–pancreato–biliary (HPB) Surgeon or Cardiothoracic Surgeon, depending on where and how extensive the endometriosis lesions are. These lesions on the diaphragm can often be managed with minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopic or robotic laparoscopic-assisted) by a skilled team. They will carefully remove superficial lesions or, if needed, perform a resection of full-thickness areas of the diaphragm, as seen in Images 7, 8, and 9. Afterwards, the diaphragm is carefully repaired with sutures. It’s important to be aware that surgery carries some risks, such as bleeding from the liver or lung collapse, along with typical surgical risks. VATS, performed through the chest wall by a cardiothoracic surgeon, can be used to remove diaphragmatic and lung endometriosis with surgical staplers. Keep in mind that pain can be significant after surgery, and a chest drain might be needed for a few days. Sometimes, open surgery involving both the upper abdomen and chest may be necessary to ensure the best outcome.

Image 8- View through to the pleural cavity from the upper abdomen after resection of a large area of full-thickness diaphragmatic endometriosis. The collapsed lung is seen on the right.

Image 9 – Full-thickness diaphragmatic endometriosis after removal from the abdominal cavity

When surgery is performed by a skilled multidisciplinary team, the chance of recurrence is less than 5%. If it’s acceptable to the patient, hormonal suppression can be a helpful option after surgery. Just like with pelvic endometriosis, if pain has been ongoing for many years, some discomfort might still remain even after removing all visible endometriosis from the diaphragm and thorax.

Extra-pelvic endometriosis in the diaphragm and thorax is found in less than 2% of people with pelvic endometriosis, but the true incidence is unclear due to limited research. The symptoms can vary from mildly irritating to severely debilitating, even life-threatening. This kind of endometriosis can be challenging to diagnose and investigate. For those experiencing symptoms, it can be frustrating to find a team of specialists with experience and knowledge to help manage these symptoms. When symptoms don’t respond to initial hormonal treatments, it may be helpful to consult a surgical team led by an Endometriosis Specialist for further intervention.

Written by,

Dr Michael Wynn-Williams, Member of our Clinical Advisory Committee.

Revised August 2025